18 April 2019

You could go on foot, on horseback or travel in a carriage - after the invention of the wheel, the options available to humanity for overland travel barely evolved for 4,000 years. This did not change until the advent of the innovators and inventors in the late 19th century. After the railway had made it possible to transport large quantities of people and goods around in great style, it was the internal combustion engine which fundamentally transformed individual mobility. Our brief history of the internal combustion engine relates the tale of how it was invented, how it came to be used in the first automobiles and what was done to mitigate the risks associated with this high-speed mobile innovation.

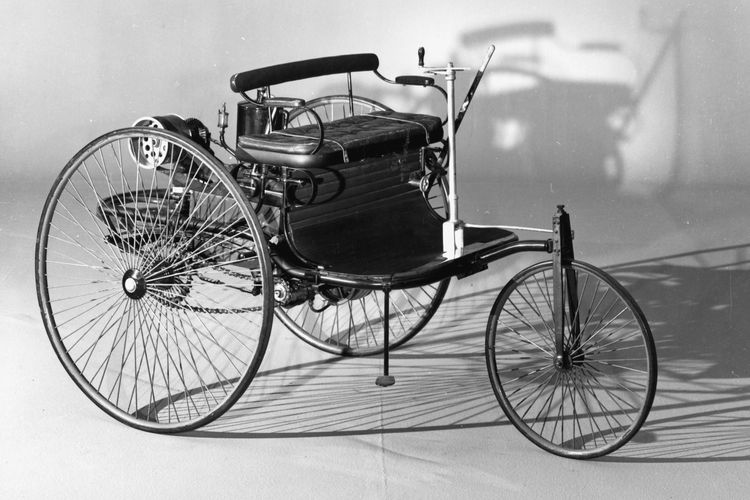

One day in August 1888, the inhabitants of Wiesloch, Bruchsal and Durlach had every reason to be astonished: A vehicle with three wheels, which looked like a cross between a horse-drawn carriage and bicycle, trundled through the streets of their towns. Except that no horses were to be seen anywhere nearby. Nor did the three passengers, a woman and two youngsters, appear to be pedalling. The vehicle was apparently travelling under its own power - controlled by a crank which the woman was holding. The woman’s name was Bertha Benz, the teenagers were her sons Richard and Eugen, and the vehicle was the Benz patented motor car No. 3.

Carl Benz, Bertha's husband, had patented the first version of the vehicle back in 1886 and introduced the vehicle to the public in July of the same year during a test drive in Mannheim. “There can be no doubt that this motorised velocipede will soon gain numerous friends,” was the euphoric declaration of the Neue Badische Landeszeitung on 4 June 1886. And yet, initial attempts to find buyers willing to invest in this “benzine carriage” fell flat, and economic success proved elusive. To revive her husband’s flagging spirits and convince their contemporaries of the practicality of the new conveyance, Bertha Benz decided to carry out a thorough test drive - albeit without telling her wavering husband in advance. First thing in the morning, she and her sons took to the 104-km road from Mannheim to her city of birth, Pforzheim, which they duly reached safely after 12 hours and 57 minutes.

This trip is regarded as first long-distance drive in automotive history and is commemorated to this day as the Bertha Benz Memorial Route. How major the promotional impact was at that time is still the subject of debate among researchers. One thing, however, is certain: thereafter, the Benz patented motor car began its slow but sure uphill journey to commercial success. By 1893, 69 vehicles had been sold, mainly in the US, England and, especially, France, where, thanks to good roads, the first car enthusiasts were not quite so thoroughly shaken about. By the turn of the century, Benz & Cie. had already delivered 1,709 specimens of their motor car. The number of employees had risen to over 430, a tenfold increase.

© akg imagesNeither horse nor pedals: The Benz Patent Motor Car Number 3 astonished in 1888 with its completely new drive.

Étienne Lenoir and the hippomobile

Carl Benz was the first entrepreneur to introduce a working automobile with a combustion engine onto the market. And yet, at the end of the 19th century, the development of the motor car found itself at something of a crossroads. Large numbers of engineers, innovative tinkerers and inventors were experimenting with engine technologies and building the first steam cars and electric cars, alongside vehicles with internal combustion engines. As early as 1863, Belgian inventor Étienne Lenoir had driven his “hippomobile” the nine kilometres from Paris to Joinville-le-Pont and back. It was powered by Lenoir’s own gas engine and fuelled by a turpentine derivative - thus earning it the distinction of the first vehicle with an internal combustion engine. Unlike in the steam engine, the fuel was not burnt outside the engine and the resulting heat directed into the cylinders. The kinetic energy was instead generated by explosive combustion inside the engine.

However, the hippomobile never made it beyond the development stage: It was too heavy, and its two-stroke engine was capable of no more than 100 revolutions per minute. Meaning that the vehicle’s average speed was around six kilometres per hour, a pace that even a leisurely stroller would nearly be able to match. Benz's patent motor car with its four-stroke engine, on the other hand, was capable of 400 revolutions per minute and a maximum speed of 16 km/h. Benz based the development of this engine on the work of Nicolaus August Otto - who had himself used the Lenoir gas engine as a template for further development.

Nicolaus August Otto and the four-stroke engine

The Lenoir gas engine, patented in 1959, caused a veritable sensation at the time and was seen as the first alternative to the large and heavy steam engine. Unlike the latter, it did not need to be preheated for quite so long before it could be put to work. Supplied with gas from the municipal grid, the quiet motor was deployed to drive such equipment as printing presses and looms. However, its construction meant that it needed a very powerful water-cooling system and, above all, huge volumes of gas. Its efficiency was between three and four percent, which meant that it could convert only a very small proportion of the energy contained in the fuel into mechanical energy.

Salesman and technical autodidact Nicolaus August Otto recognised both the potential and the limits of this machine and set about refining it. In 1861, he commissioned the construction of a replica Lenoir engine and established that it would work better if fuelled with ethyl alcohol. In the same year he and with his brother Wilhelm submitted a patent application for an alcohol evaporator. To justify the application, they cited the independence of the gas network of internal combustion engines and raised the possibility of self-propelled conveyances on country roads. In the following year he began experimenting with the four-stroke engine, a principle that had been theoretically described and patented by French engineer Alphonse Beau de Rochas in the same year, completely independently of Otto. Otto's idea was to compress the mixture of air and gas to the maximum possible extent. This would make it possible to reduce the proportion of gas and, thereby, consumption. The piston would, however, be required to move up and down twice to perform one unit of work.

In practice, controlling the combustion was still causing Otto all sorts of problems, and the experiments were culminating in the destruction of the engines. It would take twelve years, until 1876, to produce the first functional four-stroke engine in the Deutz AG gas engine factory. He established the principle of intake, compression, combustion and exhaust according to which every internal combustion engine in either cars or motorbikes still functions: In the first stroke, the piston moves down and sucks a mixture of air and fuel into the cylinder through a valve. In the second step, the piston moves upwards, compressing and heating the mixture in the process. At the moment of maximum compression, the mixture is ignited by the spark from a spark plug. The pressure generated by the explosion pushes the piston down very quickly in the combustion stroke. In the fourth step, the piston quickly moves up again and expels the burned gases from the cylinder through a valve.

Daimler, Maybach and the motor quadricycle

The engine was first made ready for mass protection by Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach, who had been in the employ of Deutz AG since 1872. The engine was a great success and sold very well. But it was still too heavy for mobile use. After falling out with Otto, Daimler left Deutz AG in late 1881 and set up an experimental workshop in Cannstadt, where he was soon joined by Maybach. Daimler's goal was the development of small, fast-running internal combustion engines that would be able to power vehicles on land and water. As early as 1883, he filed a patent application for an improved single-cylinder four-stroke engine which he had developed jointly with Maybach. Their “gas engine with hot-tube ignition” could generate 1 hp at 650 revolutions per minute. It was small, relatively light and ran on petrol: ideal for use in a vehicle. In 1885, Daimler and Maybach built the precursor to the motorcycle, which they christened the “Reitwagen”, or “riding machine”. In October 1886, they installed a “grandfather clock” engine in a carriage - thus creating the first automobile with four wheels. In 1889, they unveiled their first completely self-propelled vehicle, the 1.5 hp motor quadricyle or “steel wheeled car”, at the Paris World Exhibition. Eleven years later, they developed a car for Austrian businessman Emil Jellinek, the body of which represented a significant departure from the previous carriage principle and whose 35 hp engine propelled the car along at a top speed of nearly 90 km/h. The car was named after Jellinek’s daughter, who went by the name of Mercedes.

Driver's licence becomes compulsory

Jellinek’s Mercedes cost him some 150,000 marks. So, it was no wonder that, at the turn of the century, the automobile was still an extravagance reserved for the very wealthiest ten thousand. But even though only a few vehicles were initially rattling along the roads, they were increasingly stirring up controversy and also causing accidents. It was for this reason that, on 10 March 1899, French President Émile François Loubet chose the Journal officiel to announce the world’s first highway code and, with it, the introduction of a mandatory driving licence. The president justified this decision by claiming that automobiles were increasingly “scaring horses, damaging the ground or simply throwing up too much dust”.

Eleven years previously, Carl Benz had been granted the world’s first driving licence by the district office of the Grand Duchy of Baden. But it would take a few more years for the possession of a driving licence to be made mandatory in Germany. In Prussia, the first basic regulation for the inspection of motor vehicles and their drivers was enacted by a ministerial decree of 29 September 1903. It was the engineers of the boiler monitoring associations (DÜV) who were entrusted with these tasks. After all, many of the early cars were still powered by steam engines, with which the DÜV experts were very familiar. And yet, a regulation for the inspection of drivers and vehicles throughout the German Reich was still not in sight, even though the situation was becoming more urgent year by year. This was because the fledgling technology was susceptible to breakdown, and many drivers were not familiar with their conveyances.

© TÜV NORDTextbook for examiners from 1927.

As early as 1906/1907, the 36,022 vehicles on Germany's roads were involved in a total of 145 fatalities. In proportion to the number of automobiles on the road, the risk of falling victim to an accident was nearly sixty times as high as it was in 2017. The state had to respond. In 1909, legislation in the form of the “Act on Motor Vehicle Traffic” saw to it that safety in motorised road traffic was for the first time covered by law throughout the whole country. The regulation laid down, inter alia, the following: “The vehicles must be roadworthy and, above all, so designed, furnished and equipped as to ensure that risks of fire and explosion and any avoidable nuisance to persons and carriages from noise, smoke, steam or noxious odours are excluded.” Officially recognised experts were now responsible throughout Germany for monitoring the safety of drivers and vehicles - and among them were the experts from the DÜV. They were initially able to carry out this task in addition to their other inspection duties, because, after all, in comparison to steam boilers, the number of cars and their drivers was still vanishingly small.

From luxury good to mass means of transport

That this would soon change was in no small measure down to Henry Ford. In 1913, the American car magnate installed assembly lines in his factory in Highland Park, Michigan, thereby revolutionising the manufacturing process for his Model T. As the production costs plunged, so too did the prices. Ford's robust and easy-to-repair “Tin Lizzy” became a bestseller, selling some 15 million times by 1927. Other automakers, too, learned from the Ford principle and said goodbye to manual production. In Paris, 100 Citroën type A cars had been rolling off the assembly line each day since 1919. In 1924, in Rüsselsheim, Opel ushered in the age of industrial production in Germany with the production on conveyor belts of the “Laubfrosch”, or “treefrog”.

As the number of cars grew, so too did the need for inspections. In the early 1920s, therefore, Norddeutsche DÜV set up its own automotive department, followed in 1928 by DÜV Hannover. As the boiler monitoring associations were now also carrying out safety tests of lifts and electrical systems, the decision was made to change their name in 1938. They were henceforth known as “Technische Überwachungsvereine” (“Technical Monitoring Associations”), or “TÜV” for short.

At this time, however, the requirement was for cars to be inspected and approved once only, at the time of first registration. Nonetheless, many fleet owners still wanted their vehicles to be regularly checked by external experts. After all, if a lorry were to break down on the road, it would cost money to fix. Private motorists initially had little interest in voluntary security checks, even though police controls repeatedly showed that, on most vehicles, neither the brakes nor the lights were working properly.

The TÜV becomes due

After the war, the car slowly but surely blossomed into a mass means of transport and becomes a mobile symbol of growing prosperity in the period of the economic miracle. In Munich alone, the number of cars on the road grew at 20 percent per annum between 1950 and 1960. The VW Beetle and, later, the Messerschmitt cabin scooter and the BMW Isetta made it affordable for workers and employees alike to own their own wheels. It was high time for the state to get a grip on the safety risk posed by unroadworthy cars. As of 1951, the new German Highway Traffic Act (Straßenverkehrszulassungsordnung) required the inspection of every vehicle every two years after first registration.

© TÜV NORDSince 1951, vehicles have to drive up to the main inspection every two years. But not all of them stuck to it - maybe the reason for the emptiness in this test center?

Responsible for the periodic inspections were the technical monitoring associations and other organisations, including the German Motor Vehicle Inspection Association (DEKRA). To accomplish this task, the TÜV engineers of the post-war period needed not only technical knowledge but also a real flair for improvisation. This was because the technical test centres built before the war had not yet been rebuilt or were too small for the growing number of automobiles: the experts were forced to resort to using railway yards and construction sites and even restaurant car parks, where they were occasionally confronted by drunk and rowdy vehicle owners. And yet, even despite the legislation, by no means all vehicle owners regularly presented their cars for the periodic inspection. To nudge the offenders into line, the obligation to carry an inspection sticker on the car was introduced on 1 January 1961. And the sticker bore fruit: In 1965, the Essen TÜV association alone inspected some 500,000 motor vehicles on a total of 24 test rigs.

© TÜV NORDDuring the economic miracle, cars become symbols of prosperity. A typical representative: the VW Beetle, here in the TÜV NORD branch Bremen.

Don't drink and drive

Thanks to the nationwide vehicle inspections, cars became ever safer - but the same thing did not automatically apply to their drivers. The tally of fatalities was increasing every year in proportion to the number of road users. The year 1970 marked a sad climax to this trend: Over 19,000 people died on the roads, and around half a million were injured. International comparisons showed that road traffic in Germany was particularly dangerous: The Federal Republic had a similar traffic density to the United Kingdom, but with twice as many deaths. To blame for this were in most cases the drivers, who drove either too fast, too carelessly or, not infrequently, under the influence of alcohol.

© TÜV NORDThe message is still valid today: TÜV NORD test facility in Rendsburg, before the spelling reform.

The technical monitoring associations did what they could to counteract this at an early stage. In 1955, TÜV Hannover became the first association of its kind to establish a Medical-Psychological Institute (MPI), whose task it was to compile reports on traffic offenders. These were, above all, drivers who had been caught drunk in charge of a motor vehicle. TÜV Hamburg and TÜV Essen soon followed suit by founding equivalent institutions. These did not merely compile reports on potentially dangerous drivers but also helped prevent them from offending: In the 1970s, the head of the MPI in Hanover, Werner Winkler, developed a nationally recognised training programme under the name of LEER. It helped car owners to come to the realisation that they could not drink and drive at the same time. Many traffic offenders initially viewed the training and the so-called idiot test that went with it as punishment meted out by the state - but the sole purpose of these measures was actually to ensure that drivers would reach their destinations as safely as Bertha Benz had done some 130 years previously.

You may also like

The oldest registered car in Germany

© TÜV NORD

It was only a few years after Benz’s patented motor car that the Benz “Victoria” first started chugging along Germany’s roads. This car, which was built in 1894, is still roadworthy - and, as of mid-April even TÜV tested. Tester Burghard Niemietz from TÜV NORD put the vintage car through its paces in the Lower Saxon town of Einbeck. With a power output of 6 hp and top speed of 29 km/h, this historic car may not be in anything like the same league as modern cars, but the safety regulations apply to all road users. Which was why Niemietz also issued the special instruction to have indicator paddles in the car. These serve as indicators, which were not yet compulsory at the time the car was made. For Victoria owner and vintage car collector Karl-Heinz Rehkopf, this was absolutely no problem. The main thing was that the oldest registered car in Germany was now permitted to take to the streets.